Schneider, Stefan: Intercultural Social Work in open and low-threshold homeless services in Germany. Warsaw 2012 (1)

Beginnings. Over the last few years, the presence of an increasing number of foreign guests has become apparent in open, low threshold and mostly volunteer-operated homeless services like drop-in-centres, shelters, soup kitchens and emergency shelters.

Beginnings. Over the last few years, the presence of an increasing number of foreign guests has become apparent in open, low threshold and mostly volunteer-operated homeless services like drop-in-centres, shelters, soup kitchens and emergency shelters.

There is no systematic reporting system about this phenomenon, but whenever volunteers and social workers meet in working groups and committees to discuss current difficulties, this phenomenon, and its related problem areas, is often raised as an issue. In a lot of cases the story is negative. The reports are about bad atmosphere, about conflicts, about discontent on every side: amongst the German service users, within the team, but also amongst the foreign service users. For example, aggressive behaviour and scuffles in the context of free food distribution, and police intervention has even been required as violence has broken out. A noticeable increase in the consumption of alcohol and drugs has been observed. And, as the number of visitors is increasing with these new guests, some visitors must be turned away for reasons of overcrowding or their own aggressive, disruptive behavior . This situation can worsen an already potentially tense and conflict-charged atmosphere.

In Berlin, in the monthly meetings of the AG Leben mit Obdachlosen ("committee on life with the homeless"), an association of more than 50 mainly low-threshold facilities working with homeless people, situations like these have been more or less regularly reported since 2006.

Emotions and Rumours. Another remarkable and salient fact is that all of these problem areas are emotionally charged on a very high level. The staff working in these services and facilities often feel overburdened and left alone (and they use the chance in the meetings to articulate themselves and to voice their troubles). The foreign guests frequently feel, and they are often right, badly treated and discriminated against. Confidence cannot be gained in this way, on the contrary, a lot of anger will be stirred up and a rejection of the Germans will follow. But also the German guests who have used the services for years feel marginalized and criticise the presence of the foreigners.

Discussions reached a completely problematic level, when rumours about some subgroups of the foreign guests circulated during the talks: rumours about organized, rogue door-to-door salesmen working with the backdrop of people begging, of street musicians or street magazine vendors. Rumours about foreign guests of night shelters working illegally and using the homeless services as cheap lodgings, who in fact did not need the help and were not entitled to any benefits and so on. In a word, the debates were in immediate danger of going down the wrong track. But, fortunately, there were always people, who insisted on a methodical precision in the description of the situations and to call in experts, who could give more detailed, more precise background information.

Simulation. To give an impression of the processes and dynamics in low-threshold homeless services, I developed a night-shelter-simulation-game in 2007. The idea, that it could be possible and also useful, to map the problem areas in night shelters, first came during an under-cover investigation in the year 2006 as I spent the night in an chronically over-crowded, mass night shelter run by the Berliner Stadtmission on Lehrter Straße. There, in the cellar used as a recreation room, I watched some guests placing three chairs together to form a kind of bed to sleep on. The bedrooms provided were all occupied, and the others were allowed to lie on the concrete floor, if they had some camping mats. Compared to that, the three-chair solution was a quite comfortable alternative. In a simulation game, it is very easy to adopt that three-chair arrangement representing a sleeping place. And so, I designed mostly different, contradictory character sketches for 4 volunteer members of staff in an emergency shelter and 12 homeless people with different problem configurations in need of a place to sleep.

But in the simulation game we managed to build 10 beds. Thus, complex areas of conflict were programmed in such a way as to come very close to the real situation inside the facilities. By means of adding only a few requirements, absolutely different outcomes for the task were possible. This simulation game was played in three run-throughs by different groups of young people, participants in a preparatory course for their voluntary social studies year.

There is not space here to describe in detail the simulation game and its order of events , but its results were remarkable, almost similar in all of its three run-throughs: in this role-playing game the homeless people whose role description included specifications about mental illness or a migration background with language and comprehension difficulities always fell by the wayside or were kicked out. In a first and preliminary analysis we can fix as an assumption, that the mentally ill and foreign homeless could be counted among the weakest and most marginalised subgroups of homeless people. In a sharp and provocative statement we could say: the problem is not foreign homeless people, it is the exclusion and marginalization of foreign homeless people that is the problem.

Experiencing and Measuring. When we tested the game in a self help organisation (mob – obdachlose machen mobil e.V./ strassenfeger ("homeless people mobilize" / "streetsweeper" street magazine)) I lead in Berlin, in the team playing the emergency shelter staff we had similar trends: in winter 2006/07 we had a more or less open debate on the whole project, that concluded that our homeless shelter was more or less a "Polish emergency shelter". The implication was: "And this is not okay!" So I suggested to the team that we do a study, not least because for the above reason, to learn more about our guests, the background to their problems, their (supposed or known) whereabouts and so on. The results of that quarterly evaluated and of course anonymously carried out survey was, that the actual number of foreign homeless people, with some variations, came to 30%. These results changed the situation of the debate completely: Why is our feeling different to the measured reality? Why does the obviously smaller subgroup attract so much more attention? Must we change our beliefs and which kind of conclusions do we have to draw? We can anticipate the outcome: that survey constituted the beginning of the end for these prejudices.

Within the general volunteer team the understanding was growing, bit by bit, of the fact that we must take care of every single homeless guest, and even those with foreign backgrounds are a special challenge rather than a special problem.

Few Suitable Data. Günter Piening, the representative for integration and migration in Berlin, reported at the 2008 annual autumn conference of the AG Leben mit Obdachlosen ("committee living with the homeless"), that, in principle, there is no database about foreign homeless people in Berlin. Nevertheless, he expected that an increasing amount of homeless people with a migratory background would appear. The reason for that is not only the expansion of the European Union and the resulting immigration. A large number of inhabitants with a migration background have also been living in Berlin for generations, and there are good reasons to predict that, in the future, some of these subgroups will become more affected by the risk of housing shortage and the loss of housing without any possibility of prevention or compensation for these communities.

In winter 2008/2009 the mass-emergency-shelter of the Berlin Stadtmission reported that 50% of its 120 places were consistently occupied by foreign homeless people. But the significance of this evaluation is relative, because the Stadtmission is run on the principle of accepting anybody and refusing no one. To form an opinion about these results you have to see that these circumstances are connected to the fact that other emergency shelters will not host foreign homeless people: either they refuse them or try and get rid of them or simply because they are filled to capacity. And, on the other hand, access to the high-level homeless services is usually blocked for foreign homeless people.

A survey, published In the year 2008 by the Berlin senate department of social affairs, reports separately that the amount of homeless people with a migratory background in facilities registered in the § 67 SGB XII Hilfe in besonderen Lebenslagen (“§ 67 social act book XII, assistance in specific situations” – most of the personal services for homeless people are subsumed in this paragraph) is 23% and corresponds to the Berlin average of people with a migratory background. The number of rough sleepers among the homeless is between 2-4,000 persons, and the number of people with a migratory background and foreigners respectively amongst them is not known.

Data like the measurement by mob e.V./strassenfeger or the count by the Berliner Stadtmission can merely give first points of reference, but the room for interpretation when benchmarking these counts against the general number of foreign homeless people in Berlin is comparatively broad.

The original and long-discussed positions on the problem show an astonishing breadth: they spread from nationalistic positions (foreigners are not wanted, the services are only for the Germans) via differentiating attitudes (only needy foreigners are welcome) through to global perspectives (low- threshold homeless services like emergency-shelters are unreservedly open for anybody, independently of the origin or reputation of the persons who ask for it). For each of these positions, there are different motivations, backgrounds and arguments and it is necessary to analyze them to understand, what exactly is the reason for the controversy. I will do that on another occasion. Instead, I would like to point out, which dimensions will start of by trying to find a constructive perspective for handling the topic of foreign homeless people in low-threshold homeless welfare services.

Caps as an option? A first, quite formal approach consists in the concept of quotas. That means, that it is stated, that a certain number of foreign homeless people should be served and that, appropriate to that (supposed) amount, an appropriate quota of places will be reserved exactly for that group. For example, if it is assumed, that the amount of foreign homeless people is one third, the strategy is to reserve an amount of one third for foreign homeless. people In a next step of development of this model it is possible to launch further differentiations along the criteria of region or nationality to the effect that, from the 10 reserved places for foreign homeless people, 4 will be provided for people form the region x, 3 for the people of country y and 2 for people from country z. In some of the low-threshold homeless services this policy indeed was discussed and, in a few cases, was established.

In fact this is more the culmination of a begrudgingly accepted fact and not a true cause for argument. In point of fact this policy represents more the strategy to react to another problem. People in unknown environments tend to make connections with people like them instead of linking with strangers. If and when foreign homeless people often appear in groups they do it less to intimidate or to exploit the services, but more following that group dynamic reflex, that somebody in unknown environments feels safer in a group than alone. That this behavior will be noticed by others in a very different sense, as a massive, intimidating performance of a strange unknown group, is one of the basic phenomena of interpersonal communication.

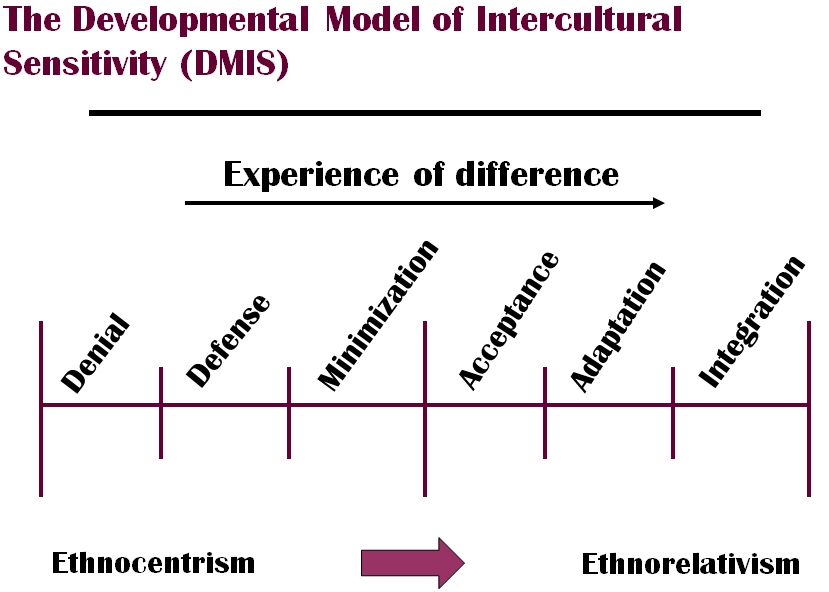

Intercultural Sensitivity. Milton Bennett, the American founder and head of the Intercultural Communication Institute at Portland State University in Oregon and one of the leading experts worldwide to the issue intercultural communication (but almost unknown in Germany) developed a model to explain this. It is called the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) and explains, that in dealing with other, foreign cultures, the experience of difference always follows the same, typical pattern. A typical first reaction to something new and unknown is to deny the significance, to refuse in believe the problem exists (denial). In a second step the existing situation will be defended and the problem will be repelled (defence). In the third step, denial or defence is no longer possible, and therefore it is tried to trivialise and to talk down the problem (minimalisation). The common thread of all these strategies is its ethnocentric position. That means, the own point of view is right, the other foreign culture is apprehended as a disturbance and a danger. In the forth step the situation changes into gaining credence (acceptance). For the first time the legitimacy of the other culture is no longer called into question. Going on to the fifth step, parts of the other culture will be considered and adopted (adoption). A first estimation emerges, and the own culture will be enriched. But, importantly, at the sixth and last step a real junction of both of the cultures will take place (integration). These three last strategies will represent an ethno-relative position. This means that, in different forms, the culture of the other could be apprehended not only as worthy of respect, but following on from that, the culture could be experienced as an addition to, an expansion of and gain for the own culture.

Grafik 1

Reflecting the issue of foreign guests in low-threshold homeless welfare offers and with a view to the pattern of Bennett could be stated, that the current situation could almost consistently be characterized by an ethnocentric attitude. The move to understanding the foreign guests as a part of the daily work is not yet part of the conceptual policy of the low-threshold homeless welfare offers. But nevertheless, over the past few years it has been possible to detect some progress. The existence of foreign homeless people and their needs is no longer denied and also the argumentative basis for a fundamental defence strategy is crumbling in the light of the ongoing process of globalization. For varying reasons there are some attempts to minimise the problem but many services try to leave behind the ethnocentric position and dare to try a new approach, based on acceptance. That leads us to two questions: what kind of challenges are we setting for ourselves and where will this road lead us to?

Intercultural Skills. Jürgen Bolten, professor of intercultural business communication at the University of Jena since 1992, has examined and explored, in reference to economic processes of transformation, what kind of dimensions are necessary, if intercultural sensitivity is seriously to be allowed and implemented on an operative level. The level of activity is the focus point for this conception. Here the dimensions will be separated into the subject-specific, strategic, social and individual qualifications. Let us have a more exact look at it: on the subject-specific level the professional relationship with the Other as the foreigner would be in the spotlight. Who s/he is, how to bridge the language barrier, what can I know about culture, tradition, economics, politics, religion, etc of the region of origin. What should I know about specific problems of the region of origin and about the concrete biography of the person I am talking to? What is the current legal position and, more importantly, what are the legal boundaries, which could be used here?

A completely different dimension concerns the strategic qualification: what kind of aims, what kind of conceptual reflections should be used to develop my facility? How can I organize the new, extended structure of tasks? Is more staff needed, new working procedures, an extended European or even worldwide network, but not on the level of the management but on the level of the direct working plane? Concerning the social level of intercultural qualification, are skills needed to recognise, analyse, interpret and communicate the various interests? Which methods, which instruments could be used to build empathy and an atmosphere of tolerance between all of the participants? Is it possible to create a mutual sense, to work on a joining vision, an intercultural outline for the daily work in the facility?

To my mind, the individual level of intercultural qualification is the most ambitious dimension, because mindsets and attitudes cannot be dictated. On the other hand, the possibility is given here to be involved on a very personal level in intercultural experiences, especially by organizing services that fit the basic needs of homeless people: It should be possible, for example, to cook special dishes from the regions of origin together with the homeless guests, and it should also be possible to install an open internet to provide contact to the region of origin, or to allow guests to watch TV channels in their language or to open up the possibility to join the team as volunteers and so on and so on.

This conception of intercultural skills presented by Jürgen Bolten is surely not to be understood in a way that would suggest that the situation of excessive demand based on globalized poverty and homelessness can simply be overcome by a diktat of intercultural expertise. It's my understanding, that this conception is rather a suggestion and encouragement to reflect, on how diverse and multilayered a process of intercultural skill development could be and that entirely different skills, interests and motivations are required of one person, one team or one organisation. It is a conception, which creates and provides space for a true diversity of activities, which could take place simultaneously, temporally shifted or interconnected with each other. It is a proposal, that everybody should join in, free of fear, but demanding an openness to processes of modifications and a lack of synchronicity too.

Grafik 2

Now would be the time to recommend a lot of concrete steps and suggestions for how a low-threshold homeless service could make substantial progress by developing intercultural skils through by easy, uncomplicated means. The contribution of Regina Thiele will continue on that point. (2)

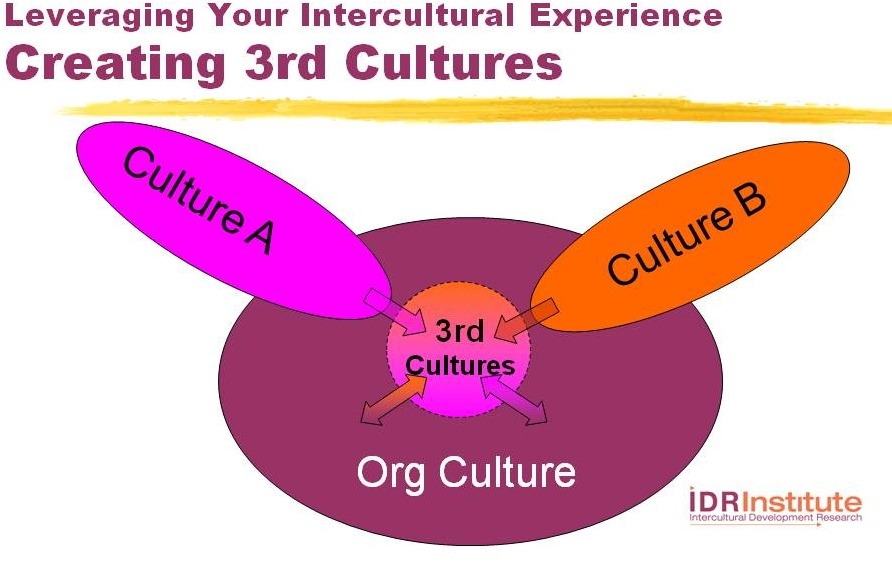

A Common Third. I will cite Milton Bennett once again. Contrary to other scientists dealing with intercultural skills, Bennett is also attentive to the possible results of this process. And he states outright, that over the course of an intercultural dialogue, a new and other culture will unavoidably arise. A culture, within which the cultures of origin are fused. A culture more rich, more diverse, more different than the previous cultures together. A new culture created out of all that which could not survive in the old cultures. Things, attitudes, settings and values which are supposed to be questioned, changed, given up, revised, extended, reshaped, improved, generalized, refined or left behind. It won't work without it. It is a high price and a challenge, which can cause a lot of angst. But, looking carefully at Bennett’s chart of the formation of a new, third and mutual culture, we see a very comforting message: there will be something left, a kind of nucleus of the former identity. Oddities and specificities, which represent the individual, the unique, the always biographical and traditional. It is this nucleus of integrity which yields that apparently balanced third culture which is interesting, diverse and manifold.

Grafik 3

Conclusions. Along the (far) way, beginning with the consideration of the concrete problems in low-threshold homeless services against the background of foreign homeless guests, we are now at the point of discussing the philosophical consequences of interculturality. The message is predictable: This process will change our lives in as inescapable and unpreventable a way as the industrial revolution did 140 years ago. There is no little bit of interculturality. Against the backdrop of the almost complete digital interconnectedness on the internet on a technical and communicative level, interculturality matches the authentic social dimension on the way towards a globalized society. Now it is up to homeless services to take this route. In spite of all these changes homeless services can be sure: the best will remain. Let us tackle it!

Dr. Stefan Schneider, European Institute of Social Science & Participation

http://www.drstefanschneider.de

http://www.eisop.org

I would like to thank Suzannah Young to bring this article in a good english version - Stefan Schneider

Sources

- AG Leben mit Obdachlosen

http://www.obdach-hkp.de/go/obdach - Beauftragter des Berliner Senats für Integration und Migration

http://www.berlin.de/lb/intmig/ - Bennett, Milton: Leveraging Your Intercultural Experience, Kyoto 2007

http://www.uniteforsight.org/cultural-competency/module6 - Berliner Stadtmission, Kältehilfe

http://www.berliner-stadtmission.de/kaeltehilfe.html - Bolten, Jürgen: Interkulturelle Wirtschaftskommunikation, Jena 2005

- mob – obdachlose machen mobil e.V./ , Notübernachtung

http://www.strassenfeger.org/notuebernachtung.html - Senatsverwaltung für Soziales, Wohnungslose und von Wohnungslosigkeit bedrohte Menschen

http://www.berlin.de/sen/soziales/zielgruppen/wohnungslose/

(1) Published first in german as: Schneider, Stefan: Interkulturelle Soziale Arbeit in offenen und niedrigschwelligen Einrichtungen der Wohnungslosenhilfe. In: Rosenke, Werena. Ein weites Feld: Wohnungslosenhilfe - mehr als ein Dach über dem Kopf bewährtes verbessern, neues annehmen, Kooperation gestalten, für Gerechtigkeit streiten. Bielefeld: BAG W-Verl., 2011, 387-396. Print.

(2) Thiele, Regina: Prozess der Interkulturellen Öffnung der Beratungsstelle Levetzowstraße in Berlin. In: Rosenke, Werena. Ein weites Feld: Wohnungslosenhilfe - mehr als ein Dach über dem Kopf bewährtes verbessern, neues annehmen, Kooperation gestalten, für Gerechtigkeit streiten. Bielefeld: BAG W-Verl., 2011, 397 – 403. Print.